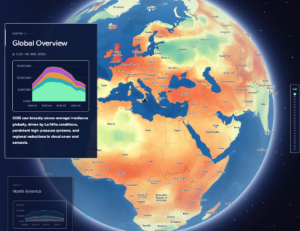

DNV’s latest Energy Transition Outlook report predicts that 79% of global electricity will come from weather-based renewable sources by 2060.

To break this down further - Solar is expected to make up 47% of the global electricity mix by 2060 - up from around 10% today and wind 32% (up from 8% today). This growth is driven by three factors:

- Cost Declines

Solar and wind are already the least expensive forms of new energy in most parts of the world. Much of this is to do with the halving of Solar’s Levelized Cost of Electricity (LCOE) over the last decade due - in a large part - to Chinese industrialisation and module production.

- Deployment Speed

Solar is the fastest new energy source to build with most utility solar plants coming online within a year of Final Investment Decision (FID). This advantage compounds at smaller scales as both rooftop and commercial systems can be installed in days or weeks. Wind projects experience lesser, but still significant reductions in deployment times compared to thermal generation, albeit to different magnitudes depending on whether it’s onshore or offshore.

- Resourcing availability

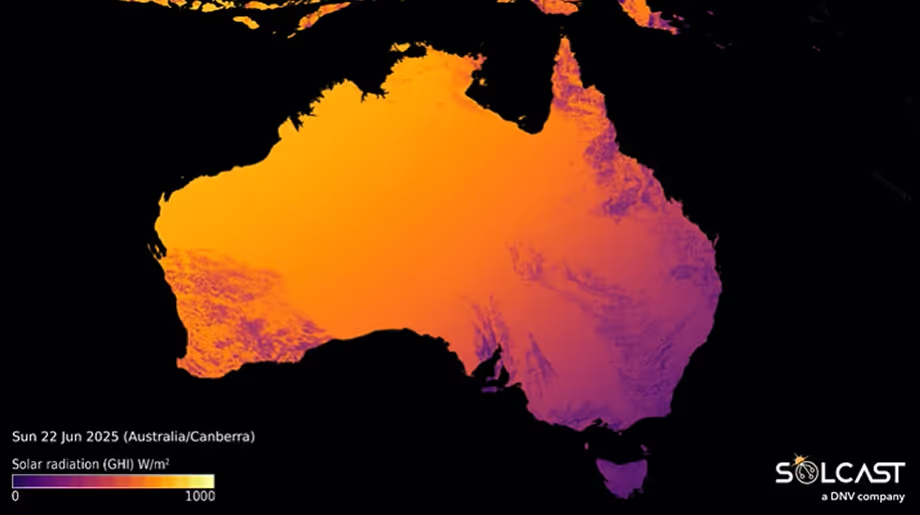

Solar resources are broadly available across most regions for residential, commercial and utility-scale installations

"The ability to deploy the same basic product on a residential roof or in a multi-gigawatt desert project allows [solar technology] to tap into a uniquely diverse investor base”

DNV Energy Transition Outlook 2025 (p.99)

While wind resources are more geographically concentrated, they still remain abundant - particularly in coastal areas, plains, and offshore zones.

But not everything is growing at the same pace - the structure of this capacity is shifting.

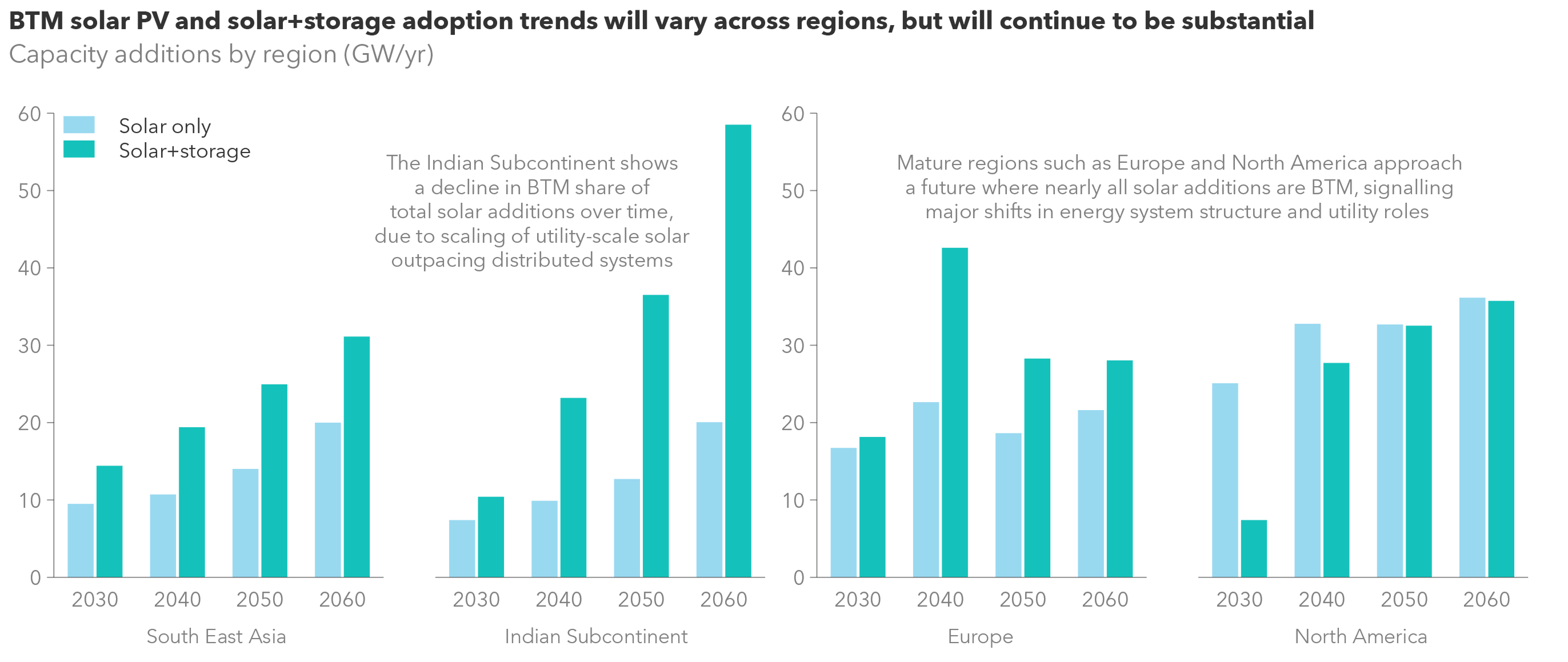

By the mid 2030’s around 50% of the new solar installations will be co-located with battery storage (up from 6.6% today) - especially in regions where the market sets the price and the capability to discharge energy in the in the evenings when returns are highest is most valuable.

.png)

And while wind remains more centralized in larger blocks, it is generally located in remote locations - both on the land and at sea, and is weather dependent - requiring management and forecasting requirements that have not been required at this scale before.

A distributed grid requires a different approach to forecasting

From consumer to prosumer

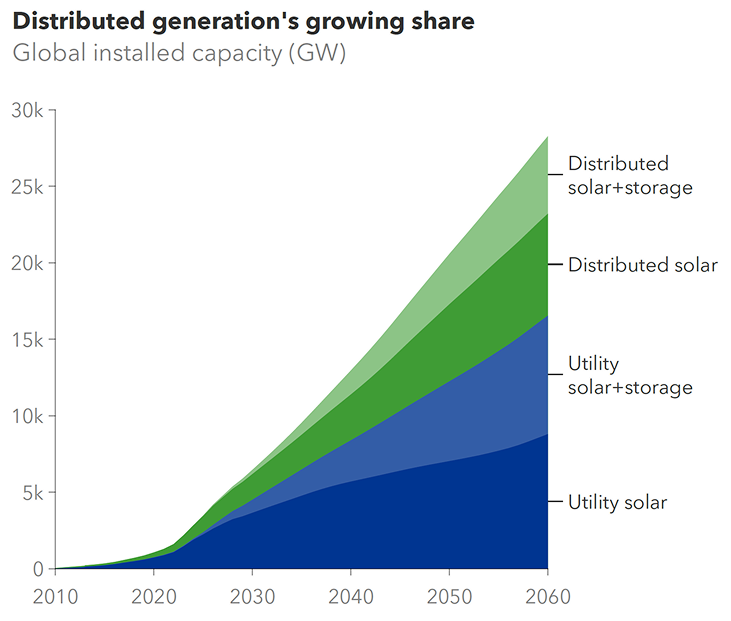

By the mid-2030’s nearly half of solar installations are forecast to be distributed generation varieties like off grid and behind-the-meter (BTM) with an expectation to overtake net utility additional installations by the 2040’s in all regions except North Eastern Eurasia and the Indian Subcontinent.

By 2060, behind-the-meter (BTM) solar will meet 13% of total electricity demand. More broadly, distributed solar generation (which includes both BTM and off-grid systems) will account for 30% of all solar electricity produced.

Developing nations especially see great value in decentralized BTM power due to its ability to reduce power bills as well as energy security from an unreliable grid.

A large share of distributed generation comes from behind-the-meter solar on residential rooftops. Rooftop solar, battery storage, and smart charging are turning consumers into "prosumers" who generate their own energy and contribute to the grid secondarily. This self-consumption-first model differs from utilities focused on wholesale grid supply, creating a structural shift in how the energy system operates.

The wind distributed story is smaller but emerging with small-scale projects contributing to the BTM/prosumer landscape in some regions.

From single-point to system-wide: how data requirements are changing

Distributed solar (and some wind) introduces a new perspective with its own unique challenges to the grid.

The data requirements for these two worlds differ fundamentally:

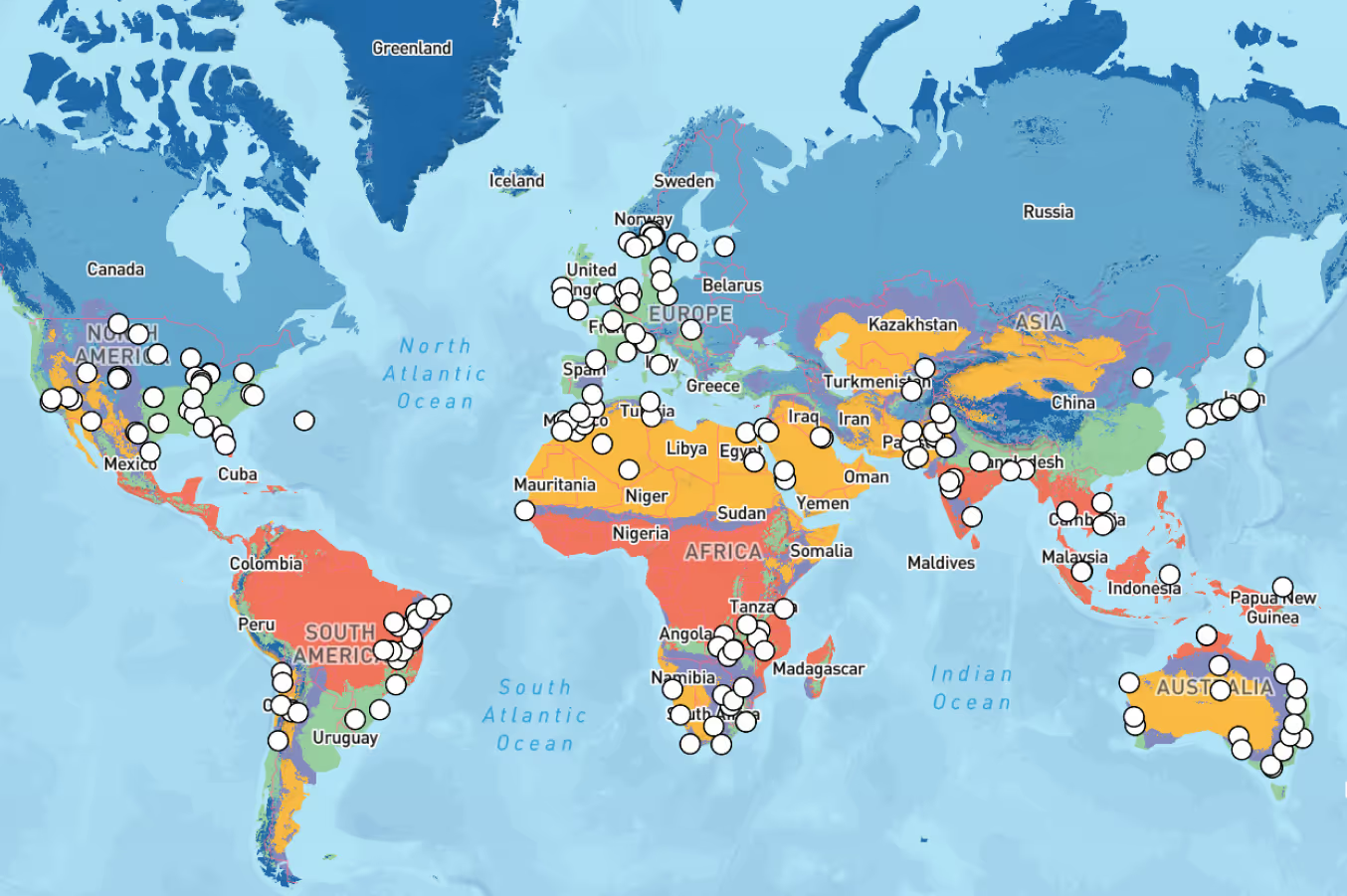

Distributed Generation (DG) challenges are rapidly becoming better understood, but knowledge is still not as mature as centralized utility-scale. And while the DG share will grow, it will not outpace centralized utility-scale - so data models supporting both are needed.

Distributed, not fragmented

Critics of renewable investment sometimes suggest that distributed renewable generation results in a fragmented grid. The term 'fragmented' implies a system of disconnected components operating without coordination - a network structure problem. But a grid with thousands of generation points isn't inherently fragmented. With sufficient observability and data infrastructure, it becomes distributed: a diverse network with coherent system behaviour.

The distinction is systemic. A fragmented network has diverse nodes but no shared state - each generator operates on local information only, invisible to system-level operations. A distributed network maintains diversity while enabling visibility and integration across the system.

This reframing matters because it shifts the engineering challenge of managing the energy grid. The problem isn't reassembling a broken system. It's building the data layer - granular, scalable, and latency-appropriate - that provides the observability required to operate many independent generators as a coordinated system.

In practice, this means moving from single-point SCADA telemetry to spatially-resolved forecasting across thousands of sites, from bespoke on-site measurement to modelled data at scale, and from deterministic dispatch to probabilistic approaches that account for forecast uncertainty.

This represents a structural shift from centralised, dispatchable generation to distributed, variable generation - fundamentally changing grid topology, control architecture, and the data infrastructure required to maintain stability.

Why this matters for grid stability

“Transmission and distribution systems built for stable, centralized power are not designed to accommodate the rapid growth in renewables…”

DNV Energy Transition Outlook 2025 (p.61)

In many regions, the grid is no longer a background enabler - it is the constraint. And as the growth of renewables accelerates it creates bottlenecks where renewable generation is available but is not able to be delivered. For example - in 2023 the UK spent USD $1B curtailing wind farms in Scotland - replacing the lost output with gas due to transmission limits. In Texas, monthly congestion costs passed USD $2bn. These costs are a direct result of electricity not reaching where it is needed despite being available.

Two paths to solving this - build transmission and manage renewables in the grid

Solutions like China’s success in prioritising ultra-high voltage lines to link remote renewables to demand centres is an example of how some countries are upgrading their transmission, but there are many grid bottlenecks across the globe that make this difficult.

Overcoming grid bottlenecks has seen success in countries that have more centralized planning and systems (like China, Turkey, Vietnam) who can avoid some frictions caused by siloed approaches with networks, permitting delays, and unclear cost-sharing rules. Transformer delivery often exceeds 3 years (8 years in Europe) unless you are China who due to its domestic transformer manufacturing and supply greatly cuts these wait times.

Finally, new generation connection requests pile up creating long wait times in the USA (median 5 year wait) and Europe (up to 10+ years median wait time).

So while we need to continue building and upgrading our transmission, we’re also able to reduce uncertainty in load management via managing renewables in the grid

Variable, not intermittent

The term ‘intermittent’ is used a lot in the energy industry as well as with the mass media - especially by those who oppose or wish to slow the energy transition, but intermittent implies unpredictable. When solar and wind are combined with storage and highly accurate forecasting it becomes more predictable.

The term ‘variable’ is becoming more widely used by those who understand and adopt highly accurate data and forecasting for their renewable generation and distribution.

Without accurate forecasts, operators fall back on thermal peakers more often than necessary, coal plant retirements get delayed, and grid planners contract excess backup capacity as insurance against uncertainty.

Wind's forecasting challenges are even more pronounced than solar’s due to wind ramps being steeper and less predictable than cloud transients. This especially applies to offshore wind farms, which are typically much larger than onshore projects, so forecast errors translate to bigger absolute swings for grid operators to manage.

Geographically dispersed wind farms can smooth some of this variability, but only with highly accurate spatial forecasting. This is where data infrastructure becomes critical.

Coordinated forecasting in practice

New Zealand's Electricity Authority recently implemented a hybrid forecasting arrangement - a centralised 7-day ahead forecast provided to all variable generators, updated every 30 minutes. Generators can use their own forecasts if they demonstrate they meet accuracy standards, creating competitive tension that drives ongoing improvement.

Early results show measurable gains: wind forecast RMSE improved from 13.9% to 12.5%, and solar from 15.5% to 6.17% in the hybrid forecasting case study.

The data layer enabling the decentralized renewables

As DG takes up more of centralised utility-scale's generation share, data requirements change fundamentally. The risk is fragmentation; the solution is a data layer that enables system-wide visibility.

What data is needed

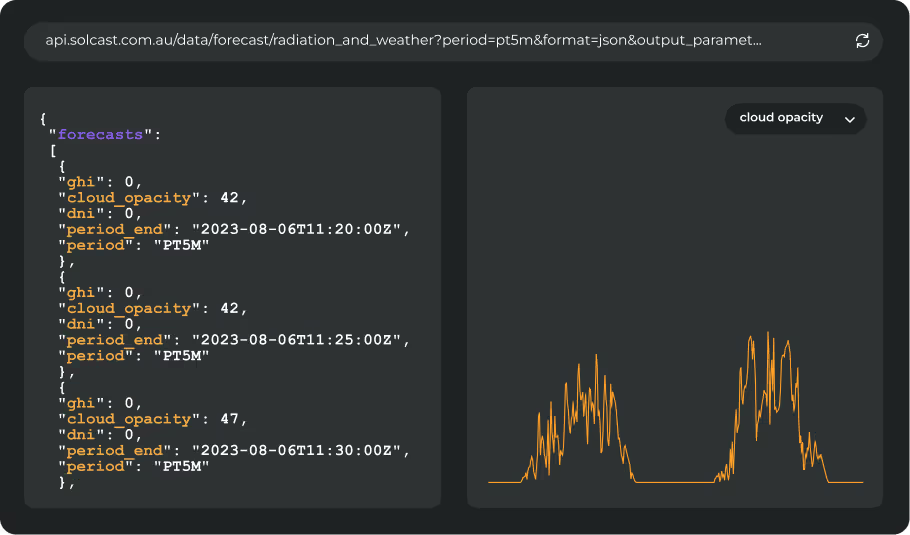

A distributed generation landscape requires data infrastructure that is granular, scalable, and accessible without on-site measurement. For solar, this means irradiance components, cloud dynamics, temperature, and atmospheric conditions - alongside historical baselines like TMY and increasingly utilized time series data for more accurate resource assessment. Wind generation requires its own set of meteorological inputs - weather data combined with measurements traditionally gathered from met masts and increasingly from LiDAR systems, plus SCADA data from operational turbines. While the data is different, both need forecast horizons spanning from nowcasting through day-ahead, with increasing sub-hourly granularity as markets move toward faster dispatch intervals. The complexity multiplies when you account for the interaction between weather, geography, and thousands of individual sites - each with its own microclimate and performance characteristics.

AI is transforming how this data is used

As the DNV ETO report notes, "advanced software is becoming just as important" (p.61) as hardware upgrades for grid management. Human-AI systems are now supporting grid operators by "speeding up power flow calculations and improving dispatch decisions, especially as the grid becomes more dynamic" (p.61). Rather than replacing existing tools, AI helps make them faster and more adaptive - reducing losses, cutting renewable curtailment, and easing congestion.

Operators are also starting to use AI to manage flexible demand, detect faults, and improve resilience. These tools can reduce the need for redundant infrastructure and help grids run closer to their capacity. But AI is only as good as the data underpinning it. Granular, high-quality resource data is no longer just useful for project development - it's becoming foundational infrastructure for an AI-optimized grid.

This data needs to be accessible

For this data layer to function at scale, it must be accessible via API - integrating directly with inverters and turbine controllers, energy management systems, trading platforms, and grid operator tools. Looking ahead, this extends to emerging interfaces like MCP (Model Context Protocol) servers, which allow large language models and AI agents to access and act on live data directly. The value isn't just in the data itself, but in its ability to flow seamlessly into the systems - and increasingly, the AI models - making real-time decisions.

New Zealand's Electricity Authority recently implemented this principle at a national scale - establishing a hybrid forecasting arrangement where a centralized 7-day ahead forecast is provided to all variable generators, updated every 30 minutes. The early results show wind forecast RMSE improving from 13.9% to 12.5%, and solar from 15.5% to 6.17%. Read the full case study

What this means for an increasingly distributed energy system

The shift from centralized to distributed generation isn't just changing where power comes from - it's changing what infrastructure is needed to manage it. A system structured around a small number of large, dispatchable plants is being replaced by one with millions of variable generators - each requiring characterisation, forecasting, and integration into dispatch and balancing systems.

DNV's Green Data Products, including Solcast, Solar Resource Compass, SolarFarmer and WindFarmer, provide the data infrastructure to support solar and wind projects across their entire lifecycle - from resource assessment and financing through to operational forecasting and optimization.